The Gambia is one of the poorer African nations, and about 75% of the population depends on crops and livestock for its livelihood. But feeding the people depends on more than agricultural methods, so here are my observations on some of the other issues.

One problem is about economic attitude. Food is exported because the pull of cash is too high. The attitude of having fun now and not saving for food tomorrow was very clear when I was there. It was Tobaski (their Christmas equivalent) and it is traditional to sacrifice a ram, so over-priced rams were bought by families who couldn’t afford it (another similarity to Christmas…). Would the situation be improved by responsible attitudes and an understanding that eating their food is better than selling it to pay for mobile phones? If we increased agricultural productivity would we just feed this problem.

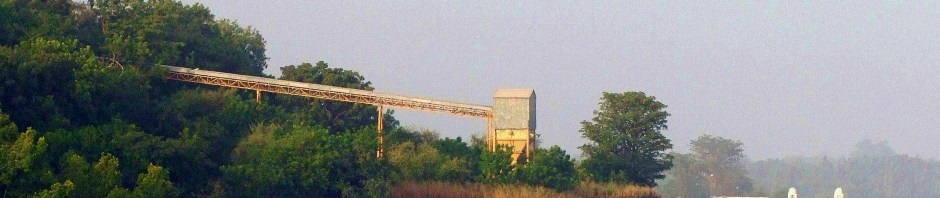

Transport is a problem, particularly in terms of food distribution. One of the main crops is groundnuts, and many villages grow a surplus. My friend reported that her village chief organises the selling of groundnuts. He ripped the villagers off, but at least they get some money for nuts that would otherwise go to waste. We saw a barge full of groundnuts come down the river one night (well OK I was fast asleep but I am reliably informed it passed our tent), and at one village there is a large conveyer belt that supposedly transports groundnuts to the river bank – that’s what you can see in the image at the top of the page.

But there are very few boats transporting nuts, and the road system is very poor. The Dutch are currently working crazily hard to build a road along the south bank of the river. But much of it is still dirt, and anyway I’ve never seen a lorry. So maybe increasing yields is no use until a transport network is built, and if we’re thinking of using GM seeds for example, we have to think about the practicalities and social impacts of distributing them. But road systems come with problems as well as benefits. Are they what we really want?

One last point – population growth. Large families are common – our guide has 7 sisters and a half brother. There are many cultural reasons for this, for example one of the tribes is particularly known for marrying young (14/15 is quite normal) and it’s common to have multiple wives. Why do we keep coming back to this point? A scapegoat seeing as we haven’t managed to fix the others, or an understanding that feeding the world is going to get even harder?

Me and some millet

I can’t see the picture of the conveyor belt – I’d like to!

Some centralised planning is important for The Gambia. I worry that, as you suggest, the Dutch road will increase access to consumer goods – or at least increase awareness of and desire for them. With careful regulation, could trade be restricted to foodstuffs and healthcare? Unlikely. It’s probably no bad thing that the construction of the road is proving difficult, as long as the financial backers will not have recourse to exploitative trading in order to recoup their expenses.

To see the conveyor belt you have to click on the post (not just view it on the home page) and it will appear as the image in the bar over the top.

Interesting point about restrictions on trade – it raises the issue of how much the developed world should play ‘nanny state’ to the developing world to avoid mistakes we have arguably made?

OK when you said conveyor belt I was expecting a little ricketty thing maybe a meter or so off the ground…that is huge!

And here we go again with there being no clear, good answers for the problems of the world. (Then again if it were simple then it wouldn’t be a problem would it?) How do we stop any good we do turning out worse than what was there before?

It might be rickety, but it’s rickety on a huge scale!

Sometimes the worry that things will turn out worse, or just having no idea how to make things better, can stop us acting. But I’m a firm believer that, over all, trying to make things better has benefits, not every time, not as good as we’d hoped, but worth it.

Thanks Emma for sending me this great link:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-11890702

“You can modernise agriculture in an area by simply building roads, so that you can send in seed and move out produce”

Roads can certainly open up markets and bring in money. It is not so clear that they will bring money to the people who are currently farming the lands. Distant markets need regular supplies, centrally organised. It’s likely that this situation will be exploited by foreign companies, who may encourage cash crops rather than local food. Desire for profit is as strong a force as the prospect of climate change.